“Independent India must choose whether we will have a people’s police or a ruler appointed police, or in other words whether the people should rule or whether the parties should rule. The Constitution has laid down that the people should rule, so the police must also be the people’s police”

– Khosla Commission in 1968

It is the Constitutional duty of the State to provide an impartial and efficient police service that will help to safeguard the interests of the people. Under the Indian Constitution, policing is a state subject and hence the state Governments are responsible for providing an efficient police force. Most of the states in India have separate legislations dealing with the control of police in that state. The Indian Police Act was enacted by the centre in the year 1861. According to Section 23 of the act, it shall be the duty of every police-officer promptly, to obey and execute all orders and warrants lawfully issued to him by any competent authority; to collect and communicate intelligence affecting the public peace; to prevent the commission of offences and public nuisances; to detect and bring offences to justice and to apprehend all persons whom he is legally authorised to apprehend, and for whose apprehension sufficient ground exists; and it shall be lawful for every police-officer, without a warrant to enter and inspect, any drinking-shop, gaming-house or other place of resort of loose and disorderly characters.

Most of the state legislations on policing are based on the Indian Police Act itself. This act was legislated for making the police a more efficient instrument in curbing, controlling and detection of crime and criminal activities. The Police Act gives each State Government the power to establish its own police force. The UPA Government, when it came to power in 2009 had announced its intention to bring in police reforms in India, but nothing has happened so far. A Human Rights Watch and People’s Watch Report in 2009 claimed that around 1.8 million people are being subjected to torture in police custody across the country. Most of the states enacted a legislation for administration of police only after the Supreme Court decision of 2006. Prior to it, only 4 states had these legislations. These states were Maharashtra (The Bombay Police Act, 1951), Kerala (Kerala Police Act, 1960), Karnataka (Karnataka Police Act, 1963) and Delhi (Delhi Police Act, 1978).

® The Supreme Court Decision of 2006

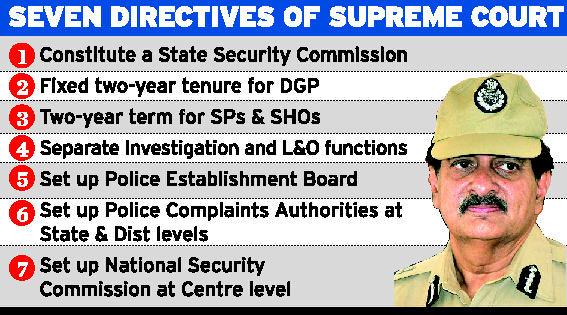

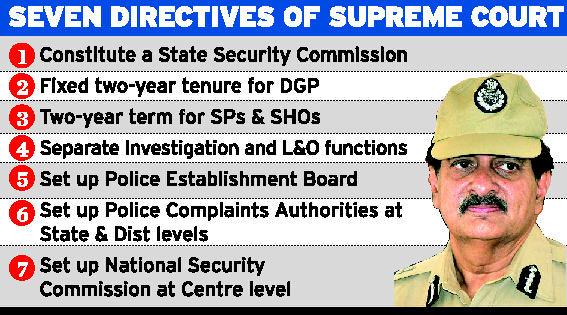

The Supreme Court in the 2006 case of Prakash Singh v. Union of India issued directions to state and central governments and tried to address the problems in the present police laws. The Supreme Court in its order asked the states to constitute State Security Commissions to ensure that the state governments do not exercise unwarranted influence or pressure on the police; to lay down broad policy guidelines, and to evaluate the performance of the state police, enact a new legislation if they do not have one. After these guidelines were issued, many states enacted specific legislations for the police force. But there have been some states who have still not complied with these guidelines of the Supreme Court. The states of Andhra Pradesh, Arunachal Pradesh, Goa, Jammu & Kashmir, Jharkhand, Madhya Pradesh, Manipur, Mizoram, Nagaland, Orissa, Tamil Nadu, Uttar Pradesh and West Bengal still do not have any legislation in place. Some of these states have bills pending in their respective state legislatures.

® A Critique of the Indian Police Act

The Indian Police Act of 1861 was legislated by the British right after the revolt of 1857 to bring in efficient administration of police in the country and to prevent any future revolts. This act has continued despite Indian being transformed from a British colony to a sovereign Republic. The National Police Commission, 1979-81 (NPC) felt the need for reform and hence it went on draft a Model Police Act in its Eighth Report submitted in 1981. Unfortunately, this proposed bill, which was developed as a response to the context of the times, and addressed to end some of the ills that plague policing has not been adopted by any state. Nevertheless, it has served as the template for nascent initiatives for many who are trying to replace the out of date Police Acts in their states with more relevant legislation.[1] A few glaring examples from the recent history of the erosion of the rule of law or of major violations of citizens’ rights resulting from the wrong type of political control over the police are the anti-Sikh riots of 1984, demolition of Babri Masjid on 6-12-1992, inaction in registering or pursuing cases of corruption, scams and frauds involving politicians. The police was also blatantly misused for political purposes during the Emergency (1975-1977). This problem of political interference was also dealt with by the NPC in its 1979 report. The National Police Commissions in 2000 identified indiscriminate arrests by the police as a chief source of corruption. The Report said the power of arrest must be used only in the rarest of rare cases and that an allegation of commission of an offence cannot constitute as a ground for arrest.

The lack of any effective accountability mechanisms and periodic review of performance is causing the police to lose confidence of the public. Another problem is that the widespread indiscipline and cavalier attitudes towards law and procedures are eroding the faith of people in the police. The people nowadays have little or no trust in the police. The Police Act, 1861 vests the superintendence of the police directly in the hands of the state government. At the present time, the Head of Police (Director General/ Inspector General) enjoys her/his tenure at the pleasure of the Chief Minister. S/he may be removed from the post at any time without assigning any reasons. Such a state of affairs has resulted in wide-spread politicization of the police where increasingly, allegiance is owed not to the law but to the ruling political elite. Another problem with the present legislation is that the only independent authority with the capacity to oversee or investigate police excesses is the National Human Rights Commission (NHRC). The Commission has the power to only advise the Government. If any state government refuses to accept the NHRC’s advice, there is no provision in law that empowers the Commission to force the government to implement its advice. It can of course approach the higher courts and seek directions. The NHRC had issued four summons to the Director General of Police, Bihar, over the last eight months for the two wrongful arrests of activists, only to be met with a wall of silence. The Government had set up the Soli Sorabjee committee to suggest police reforms and they came up with a draft bill which was never passed by the Parliament, for unknown reasons. Even the J.S Verma Committee which was set up after the Nirbhaya Rape case suggested police reforms. There is a need to bring in police reforms so that the police can be made accountable by the citizens. More power in the hands of the police will not help, but more responsible use of the abundant power that they already have. The Police Act, 1861 needs to be replaced with legislation that reflects the democratic nature of India’s polity and the changing times. The Act is weak in almost all the parameters that must govern democratic police legislation.

LawSikho has created a telegram group for exchanging legal knowledge, referrals and various opportunities. You can click on this link and join: